With Halloween approaching and spooky monsters on the rise, now is the perfect time for stories about classic monsters. Tor.com is happy to present “Ramesses on the Frontier,” a new story by acclaimed author Paul Cornell from upcoming mummy anthology The Book of the Dead. This anthology, the first ever book of original mummy stories, is published by Jurassic London in cooperation with the Egypt Exploration Society, this anthology features stories by Gail Carriger, Jesse Bullington, Maria Dahvana Headley, Maurice Broaddus, and many more. You can see the table of contents and get information on how to buy the anthology here. A portion of all proceeds from sales of The Book of the Dead will benefit the Egypt Exploration Society.

Paul Cornell’s story follows Ramesses I, founder of his dynasty, on his journey through the Duat to earn his eternal reward. To the great confusion of Ramesses, however, the Duat is not what he had been led to expect. He must travel across America, at the turn of the new millennium.

Imagine Pharaoh Ramesses I, first of his dynasty, the father of imperial Egypt, being kept at the Niagara Museum and Daredevil Hall of Fame in Ontario, Canada. Ramesses himself can’t. He lies in a stone casket, not his own. Only a rope strung between two sticks stops the casket from being interfered with. A sign nearby proclaims something in livid letters that he can’t read. He’s been put on display with several others. These include a man with two heads (one of them added post mortem, Ramesses has looked closely and seen the stitches), an unfortunate with some sort of skin disease that gives him webbing between his fingers, and something with a thick coating of fur, preserved under glass. To be arranged with them annoys Ramesses. One of these things is not like the others, that’s what he wants to shout. These are dead bodies that have been defiled. He is… well, he’s not quite sure what he is right now, but he has the powers of awareness and motion, and these sorry bastards don’t.

He keeps wondering if something went wrong with his funeral rites. He’s sure his ka, which left his body at the moment of death, has been provided with excellent refreshment. And many spells had been written and placed to allow him to deal with the problems of the afterlife. He examined the lists himself, just days before he went to bed for what turned out to be his final sleep. There had been a great rush to get it all done. He’d only been Pharaoh for a few months before his illness, and they’d only made a small tomb as a result, but he’d been told that everything was ready. His son Seti had repeatedly assured him. But here he is, feeling like he’s still in his body, but with his body being a… well, Ramesses isn’t really comfortable thinking about that.

His ka certainly left, because he remembers the moment of his death, him looking up at his beautiful son, and darkness moving swiftly in from the world all around his eyes. His ba, the record of his ethical efforts, is supposed to have stayed attached to his body until the correct ceremonies were performed, but there’s no way to tell if they were, because he’s as unaware of his ba now as he was in life.

If that new High Priest got that bit wrong, then perhaps that’s why he’s more like a corpse than an akh. This is definitely not what he was expecting.

He’s sure that whatever’s going on here, he won’t be here forever. But time does seem to be stretching on, and nothing much seems to be happening. When he was High Priest, he put the correct religion back in its rightful place. The gods owe him. So what’s the hold up?

It’s not just himself he’s worried for. It’s his people. The nation of the river, the mirror of heaven, depends upon him completing this journey in order for others to follow. He is their ambassador. He changes the way as he passes through it. He makes it easier, like someone who stamps down reeds as they walk through a marsh. The rest of his folk who’ve died will be backed up by now for… well, who knows how long he’s been here? The halls have certainly changed during that time, but they might change continually. He walks at night, but he doesn’t know if that’s every night. He only feels it is night because the mysterious lighting is kept so low, and he has a vague awareness of there being times when it’s been brighter.

So that’s his situation. He’s awake again tonight. He’s stuck. And he can’t find a god to complain to.

As usual, he cautiously pulls back the lid of the casket, waits for a moment to check that there is only what passes here for silence, and climbs out. His feels the ache in his back. He sighs. He wonders if there is ever, actually, an end to pain. He sometimes thinks that’s his punishment, but it’s really not much of one, is it? And one should be aware of justice having been done to one, not just wake up in jail none the wiser. When he sent those sun worshippers running, he made damn sure they knew what was being done to them. Don’t be such cowards, he bellowed at them, Ra will be back tomorrow, and it’s the other gods you should worry about. The people applauded him and threw things at the sun worshippers as they ran from his soldiers. A great day.

Ramesses realises he’s allowed himself to become lost in reverie. Again. This is no good. His mind is a little foggy. But maybe that’s only to be expected, considering how far he is from his organs.

He goes for a wander.

He walks through the vast, quiet halls, looking up once more in undiminished awe at the crystal ceiling, the flowing images that are somehow pinned to the walls, put inside frames like important declarations. This building, so reminiscent of a tomb, must be the Duat, the underground world where spirits and gods come and go, which leads to final judgment. The images on the walls are one piece of evidence that points to this theory being correct. What he’s seeing there are perhaps those caught on the way, because of his own predicament. He sees the same faces many times. They are mostly faces that are rather like those of Syrians, but paler, which is a bit weird. Perhaps that’s just who was coming across when he got here, when the system seized up. It is a little surprising that these unknown races should be involved. That they should be depending on him. But pleasing, in a way. The true religion must be true wherever you go. His river people are ahead in that regard. At least, they are now he’s gotten them back on track.

The pale people’s clothes are bizarre. Ramesses assumes that their dream selves are being examined alongside their lives. There is no other explanation for the impossible wonders. Whoever these foreigners are, he’s pretty sure that if they could, for instance, fly by the use of machines, they would have jealously come and taken the land of the river. He shivers at the thought of how many of them there are, and how strong. He’s glad they’re dead now, and not about to invade his beloved land. But still, he’ll put in a good word for them. They seem fun.

Ramesses moves on.

At the end of the central chamber, there are a series of paintings, rendered to a high degree of detail, most of them oddly not in the colours of life but in blacks and silvers. Perhaps the artist only had those available. They show the great river that must be nearby, the sound of which Ramesses can sometimes hear when the halls are relatively quiet. In the pictures, souls are either in the river, or in containers placed in the river. These are very like the vases that, back in his grave, contain his own internal organs, assuming that new High Priest got that bit right. The pictures show people getting into these containers and being taken out of them. There are a few on display – just the remains of them, with no sign of the soul inside. All of them are pictured in the vicinity of a thing Ramesses has only heard of, but never previously seen: a great downward plunge of water, foam and rising mist.

He stands there staring up at the perplexing images. What is he supposed to do? What is he missing?

There are doors that obviously lead outside, but he has put his ear to them, and heard strange blarings and screamings every time he has done so, surely the wailings of those who haven’t been allowed into the Duat. One is not supposed to arrive in the Duat and then simply leave. If he could find just one minor god, he could indicate to them that the Pharaoh is here, and they would surely realise that something has gone wrong and remember their obligations. He would be gracious. He would say hey, mistakes happen. They’d be tripping over themselves with an urgent need to put right this terrible faux pas.

He stops beside one of the upright walls of crystal and considers himself. He is not what he was. He looks as hollow as he feels, well, as hollow as actually, he is. His arms are used to resting across his chest now, so accustomed to the position that, whenever he gets up, he fears he will break one of them. His eyes have narrowed to slits, so he looks permanently like he’s holding in a laugh, which isn’t how he feels at all. His nose, which used to be so fine, looks like it’s been broken in a fight. His neck is thin, like that of a strangled goose. At least his temples still remind him of himself. He still has wisps of hair, pushed back from his bald patch. He touches them sometimes. They remind him of touching the head of Seti, of smelling that scalp when the kid was newborn. His own head is that soft now. All that’s left of his wrappings, so carefully prepared, are a few rags. They do not preserve his modesty. Not that he’s got much to hide. His legs are so thin it’s like walking on stilts. His hands are all knuckle. He holds one up and looks at his palm. It resembles papyrus. He is a scroll that has been filled with writing, and is now crisp out of its jar, and yet still he knows too little. No scroll knows the information it contains, he thinks. And all he wants is to be read.

No. He wants to see Seti again. He wants to touch his hair instead of his own.

There is a noise from behind him. He realises he has been so lost in his thoughts that he hasn’t considered the possibility of him not being alone in the halls tonight. This has happened on a couple of previous occasions. The first time he saw the lamps he wanted to stop their owners and question them about where he was and what he could do to continue, but then he saw that those carrying the lamps were of the same people he’d seen on the walls, and realised that they must share his predicament, rather than be responsible for it, and not wishing to be weighed down by questions he could not answer, he’d avoided them. He’s done so ever since.

But now the sound is so close that he’s not sure he can avoid it. The light from the lamp is all around him.

He summons his regal bearing, highly aware that he is naked, and turns to see the newcomer.

Ramesses is relieved to see that this is not someone of an unknown race who is staring at him, but a Nubian woman. Finally! Here is someone who might understand how he came to be here. Perhaps they can share information, see if any new conclusions can be drawn. Ramesses raises his hands to call for silence, but then remembers, ridiculously, that he can’t speak, that his tongue is still with his organs in their jar.

He attempts to speak anyway. He manages to summon a sound that vibrates like breath in his chest.

“Arrooooogghhhhhh!” he says.

The Nubian stares at him. She’s playing that lamp in her hand up and down Ramesses’ body as if what she’s seeing might change any moment. He should tell her that in his condition that’s pretty damn unlikely.

She finally says words that Ramesses doesn’t understand. “You better come talk to my supervisor.”

And then, bewilderingly, she turns around and starts to walk away. To turn her back on the Pharaoh! Ramesses can’t quite take it in. In his working life he has seen comparatively few backs. He keeps his arms in the air, and repeats his opening statement, that takes such an effort of will to generate. “Arrooooogghhhhhh?!”

The Nubian looks back over her shoulder and gestures to Ramesses with a crooked finger. He is, it seems, to follow.

Ramesses bridles for a moment, but then decides. He won’t let pride get in the way of the first sign of progress since he got here. Putting stilt leg after stilt leg, trying to keep up with the Nubian, he follows.

They reach a small lighted enclosure, in an area that Ramesses has never explored, because it has always been full of foreigners. “Seth?” calls the Nubian, opening the door.

Inside the enclosure sits a Nubian man looking at unbound sheets of papyrus with the black and silver drawings on them. A greyhound sits at his feet. The dog is attached to his chair by a leather rein. It’s looking imperiously at Ramesses, and now so does Seth. “Ah,” says Seth, looking up and seeing Ramesses, “there you are. Finally.”

Ramesses still doesn’t understand a word of what’s being said to him.

Seth reaches beside him, picks up a walking stick, and uses it to slowly get to his feet. Ramesses recognises the walking stick. It has a slim handle and a forked base. Ramesses smiles, opens his arms. Here he is! Finally! Seth goes to a cabinet, opens it and finds something. He hands it to Ramesses. The Pharaoh peers at it. It’s a small, hard cake, with the image of a dog imprinted on it.

Apt. Ramesses wants to indicate that he has no tongue, but he assumes that the god Seth, bearer of a Was Staff, knows that. He puts the cake in his mouth and does his best, with so little water in him, to give it a good hard suck. As he does so, Seth starts talking, with little hand gestures that seem to say that it doesn’t matter much what he’s saying….

“… the god of foreigners, and so it’s only apt that I’m in charge of—ah, okay, now you can understand me. Great.”

Ramesses suddenly finds that, though he still has no tongue, he can talk properly too. “Have you been here all this time, Seth?” he says. “I consecrated my son to you, and still you didn’t come to find me?”

“It was you who didn’t come to find me.”

Ramesses holds himself back. He’s speaking, unlike at any other time in his life or afterlife, to an equal. So he must be diplomatic. And he knows Seth can be tricky, can be about storms and the chaos of the world, about what’s over the border. That’s why, while he was in the land of the living, he put in a word with him by naming his son that way. “Okay,” he says, “well, putting that aside, maybe you could answer my questions now. How long have I been here?”

Seth looks at his watch. “Three thousand, three hundred years, give or take.”

Ramesses frowns. It makes his brow hurt. “But… it doesn’t feel like—”

“You’ve only been in this building for the last one hundred and thirty nine years. You were taken from your tomb by thieves. All part of the great design, but of course they can’t know that, so the usual curses have been bestowed upon their families.”

Ramesses wants to say that he’s very much in favour of that, but he’s been struck by what Seth said a moment earlier. “This… building?”

Seth sighs. He goes to another cabinet, and pulls out a rolled up piece of papyrus of a sort which is familiar to Ramesses. It’s stored a bit offhandedly, but the Pharaoh stops himself from saying anything; the gods can keep things any way they like. Seth unrolls it onto the table.

The Nubian woman who led Ramesses here joins them to look down on it also. “I’m Mattie,” she says. “If you’re a good boy, you might be seeing me later.”

Ramesses gets what she means. He nods his understanding.

The scroll turns out to be a map. Ramesses’ gaze immediately seeks the river of his country and the green around it, but although he finds many rivers, none are the right shape. In fact, he doesn’t recognise a single geographical feature. He can’t even find the great waterfall that he’s heard outside.

He looks up and sees that Seth is smiling at him. “You got separated from your coffin book,” he says. “So I thought I’d show you our own Book of the Dead: a map of the United States, circa 1999.” He puts a cook’s relish into the pronunciation of each meaningless digit. “That’s what the locals call the Duat and that’s the year by their calendar. The Duat, you see, extends far beyond the walls of this building. In fact it only properly begins just south of here. We’re in its hinterland, another country.” His finger stabs down and down and down, faster than Ramesses can follow. “Over here’s the White House, here’s Disneyland, here’s Canaveral, here’s Graceland, here’s Nashville.” The finger spins. “In the air above it all, fear of the future, which is starting to crystallise as…” He spreads his palms wide to create a shadow with wiggling fingers on the map. “The Millennium Bug!” He laughs. It’s not a nice laugh. “What the future actually holds for them… well, that’s in the next drawer!”

Ramesses tries not to frown again. “You speak as though this is a real nation, with real subjects.”

“They do think of it in that way, yes,” he chuckles.

“So… if all this is the Duat…”

?Seth nods. “You haven’t started your journey yet.”

“Why?”

“Because the Duat is the land of opportunity, a mirror of the mirror of heaven, and you’ve done nothing to take advantage of the opportunity you’ve been given. You were separated from your grave goods, which is where your ka goes back to during the day. And I’ve come back here night after night waiting for you to make your first move. In that time I’ve seen so many other guys get to where they’re going—”

“My people—”

“The ones who died after you did are in a holding pattern. They’re fine. The ones born after you died went on along after the next Pharaoh, your son.”

“Seti has already—”?

“He has indeed. And many others after him.”

?“What must I do?”

?Seth gestures at the map. “I’ve let your ba go on ahead, as far as it can. Catch up to it, where it’s waiting for you, at the Weighing of your Heart.”

Ramesses leans closer, to where his thin eyes can see the words beside the geographical features, and he finally sees something he recognises. He finds he knows many of the inscriptions. They are familiar from the Books of the Dead he has seen prepared for others. So here are destinations. But they don’t suggest a path. He is aware now of the shadow of the rest of his people, falling on him from behind. He is not even on this map yet. He doesn’t know where he’ll enter or how. He looks up at Seth again. “If I open the doors and go out there…?”?

“You’ll find your way. During your lifetime, you always had a map that led you along. But here, you’ll be lucky if you can get a few pointers. It’s all up to you. That’s the way we made it. Go out into the world of the day. Go to America.” And before Ramesses can take another look, he rolls up the map again, and puts it back in its cabinet. Then he looks back to the pharaoh. “You move on now.”

And the dog even barks in warning.

It’s winter here, he’s told, so the day of these people’s calendars will begin while it’s still dark. Ramesses will be able to leave when the doors are opened, when he would normally be driven back to his bed by the noise.

So Ramesses waits, standing around the halls a little awkwardly. Then, when the big doors are opened, and these pale people, who live, unknowingly, right next to the Duat, and are coloured fittingly for a life in shadow, start to flood in, he boldly marches towards them. Some of them scream and point, but some of them laugh, or even, more suitably, applaud. The eyes of children are shielded from him, but he suspects that’s not because of his magnificence, or his fearsomeness, but because of his tiny genitals.

He steps bravely out into this new world and winces. Oh, it’s a bit cold out here. He sees that the screams he heard are mostly the sounds of unusual vehicles. But under that is a bigger sound.

He goes to see the waterfall. He stands there for quite a while, letting the spray moisten his face. He finds a smile cracking his lips. This is great. And he’s full of hope, because he finally has a way.

A few passers-by actually ignore him when he asks which way America is. He’s not so bothered by that, just pleased that he can make himself understood. Eventually there’s one who points him in the right direction before hurrying away.

He spends several fruitless nights trying to get through customs. The guards at the gates turn him away and threaten him with arrest. He explains that he is the Pharaoh, that he is trying to save his people, but this does not impress them.

But he was not Pharaoh for nothing. He goes further away from the gates, into the streets and the buildings, and steals a coat. Then he tries the gates again, but is once more turned away. This is only to be expected. The journey through the Duat is all about getting past gates and those guarding them. During the days he sleeps in parks or in the gaps in the great stone palaces. Nobody bothers him. He wonders if this is part of his test.

He has an idea. He tries to find one of those urns he saw in the pictures. But those he sees are in strange contexts, unsuitable for his needs. Finally, he decides he can do without. That night, he steps over the low wall by the riverbank. He has never learned to swim, but it can’t be as hard as all that, and will not be required for the hardest part of this.

He floats, initially quite slowly, downstream. He is aware of cries from the bank as people notice him. The roaring of the great falls gets ever closer. He speeds up. He paddles a bit to make it faster. There are flashing lights by the side of the river now, but it’s too late, the spray is upon him!

He falls, laughing. He has passed the first gate!

He lands in the Duat in a deep pool. He waits. He does not need to breathe. He finally bobs to the surface a long way downstream, and is surprised to see the angry lights there too. He pushes at the water, and manages to head for where a group of trees stands beside the river, in some sort of park.

He struggles out of the river, and is away into the darkness before the guards can find him.

He is now in the Duat proper. The land of the souls that are free from their bodies. Not that they know it. He doesn’t need very much. He doesn’t get very much. He clothes himself by stealing, and drinks water from public fountains, merely to keep the power of speech. He expects the people here to be much more scared of him than they turn out to be. They can accept, it seems, almost anything. It helps that they will actually turn away from him rather than scare themselves by looking closely. It’s just as well they’re so hard to scare. But like animals that are hard to anger, Ramesses thinks, actually pushing them to that emotion might be a very bad idea.

He remembers a few things from the map. He knows where the challenges he must overcome can be found. And now he can look at other maps, and knows he is at the top, and presumably has to make his way to the bottom, as the country gets narrower and narrower. It is like being born again. And there was one name in particular that was meaningful to him on that first map, and so he must go there.

But there’s something that worries him. “The world of the day” was how Seth described this place. That sounds worryingly like sun worshipper talk. And everything Ramesses sees of religion here suggests that is indeed the case. The false belief has flown here and taken root! And of course it suits the Duat, all these souls on the edge of hysteria, every moment seeking escape, angry with their lot without fully understanding their situation. He passes gigantic fields of worship, open to the sky, shining huge lights upwards at night in hope of the sun, from which he can hear the cry of “Ra! Ra! Ra!” He allows himself a painful frown.

Ramesses initially assumes it’s his task here to once more drive the sun worshippers out, and so bursts into one of their temples and starts yelling, but he’s repelled by sheer force of numbers, and threatened with the arrival of the guards, and worse still, invited to submit to the embrace of these heathen ways. They say they want to listen to him, but having heard him, finally decide they don’t.

He falls onto a very finely cut lawn and is sprayed with water from something like a snake. He is gone before the guards arrive.

He’s not here to learn that sun worship is true, is he? That’d be awful. But one thing he has discovered is that he’s definitely not here to push the reeds down before him. Rather, it’s like he’s leading his people across a swamp. He must tread carefully and listen to local advice.

He makes his way down the country, night by night. He has to take many side- trips and excursions, dictated by the passage of the vehicles on rollers that he sneaks on board, or the wagons with drivers that he requests access to with a gesture. Those conversations are extraordinary. The drivers always assume he is something from their mythology, or something they can make money from. Because they have money here. When he tells them the true nature of their world, that’s it all in the service of something else, they simply don’t believe him.

He is not allowed access to the White House, where the guards tell him that instead of talking to the elected head of the peasants here, he should put his question in a net.

He asks around about that, and spends an evening with the god Thoth in a place that he is told is called Radio Shack. Thoth goes on a bit, but gives him a spell jar that is small enough to put in his pocket. He uses the spell jar to “download” and “update” all of the spells that are upon him, which he is pleased to see are still in place. One of them is a compass, which allows him to better navigate the Duat. Thoth’s whole tone suggests that a moral conversation is beneath him, so this time Ramesses doesn’t even try.

In Nashville, he wins a musical contest in front of an audience against a man in a wide-brimmed hat who, once backstage, identifies himself as the terrifying He Who Dances In Blood, a figure Ramesses is familiar with from many Books of the Dead. He tries to tell Dances that he’s learned a moral lesson about humility, but Dances just looks at him oddly.

At Graceland he fights an army of warriors, all dressed alike, flinging them into each other, delighting in his martial grace, taking their songs for his own. “What did you stand for?” he asks the fallen. “What can I learn from you?” They all start to answer, but their answers are all different.

At Disneyland, he meets with He Who Lives On Snakes, who has a giant orange and white head, and a fierce tail, and keeps insisting that the most wonderful thing about him is his uniqueness, which is hardly the case. Every question Ramesses asks him about what his next test will be is met with a reply formed in cryptic poetry. Again, Ramesses tries to suggest that he’s becoming a more moral character through these tests, but the answers he gets aren’t receptive to that idea.

At Canaveral he is spun round and round by the goddess Nut, who every now and then allows those who live here to pierce her body, and tries to persuade them that they exist in a world which has no meaning, while everything else here says the opposite, thus torturing them with doubt, a nuance Ramesses can’t help but think of as cruel. He tries to tell Nut he’s learnt an important lesson, but all he does is vomit.

Finally, he makes his way to the lower left coast of the Duat, where the kidneys should be, and there finds the building with the title he recognises: “the SETI Institute.” It must be named, he’s sure, in honour of his son. It is unfortunate that he gets there as the sun is coming up, and so Ramesses falls asleep on a chair in the waiting room. When he wakes, he is in a room festooned with the instruments of torture, and he shakes until he realises that there is nobody here, that they have taken him as a corpse, that he interested them. He is sure this must be where he is intended to be, that this must be an important test on his journey, and so he waits until the peasants arrive once again, and then announces himself.

This time, they scream and run. Which is pleasing. But then they slowly come back, and remain interested. And that is even more pleasing.

He scares and interests them in equal measure, not too much of either. This, he thinks, might finally be the lesson he’s meant to learn. He is only disappointed that his son isn’t here.

This is how Ramesses ends up on Eater of His Own Excrement’s chat show, carefully not quite explaining his mysterious origins, saying he’s “from time as well as space” and wearing, after an intervention by an anxious wardrobe department, a clean, over-the-shoulder set of what the Pharaoh gathers are bandages.

Eater treats Ramesses as if he knows the answer to everything, which suits him down to the ground. “I see… the Millennium of your people will pass without an attack from this creature you call the Bug.” This gets as much laughter as applause, which puzzles Ramesses, but he nods along, he’ll take it. He’s asked what his own beliefs are, and what he makes of the old time religion in the States. He lies enormously, saying he believes much as they do, and that all people should be free to worship as they wish. He manages to stretch out a gummy grin, which is really painful.

After the show, Eater shakes his hand and says that he’d be happy to send Ramesses on to his final destination by private helicopter. SETI will be angry, but with nothing but his own authority to go by, he’s decided Ramesses is a person, not property. Ramesses feels elated and terrified at the same time. He runs to the helicopter pad, turning down autograph requests as he goes, waving to a crowd that’s still screaming, but now not in fear.

And so he lands at the southernmost end of the country, in New Mexico, at the Acoma Pueblo, which, he is told, is “the town in the place that always was.” A figure stands tall under the whip of the helicopter blades, and Ramesses is relieved to see that it’s Anubis, actually wearing an appropriate head dress, dogs barking around his feet, and he’s carrying a Was Staff too.

“This is where they keep what they think of as the truth,” the god explains, leading him into a small pueblo hut. Ramesses looks around for a moment before he ducks inside, and sees the faces of the Acoma tribe, with all sorts of expressions suggesting interest and lack of it, involvement and lack of it, as real as life.

Inside the hut stands Osiris, green-skinned, his legs wrapped, holding his crook and flail in the posture of a Pharaoh. Ramesses relaxes. It really is time, and he’s ready. “We’ve had your ba here for some time,” says the god, unrolling a scroll and raising an eyebrow. “And when we heard you’d finally gotten around to gracing us with your presence, we sent ahead for your heart.” And there it is, in his hand, a tiny shrivelled apple of a thing.

And now Ramesses is afraid again. For himself, and his people, and that he won’t see his son. He can hear movement outside, a siren again; a shadow is cast through the door onto the wall. It’s Ammit, the devourer, the end of the world, ready to take him.

Osiris produces the scales, and puts the heart on one of them. Ramesses gets out his spell jar, and switches it on, fingers fumbling with the tiny glyphs on the screen. Osiris makes a movement of his fingers, and produces a feather from the air, that is the goddess Maat, also represented by a glyph. It’s good to see Mattie again. The green god puts the feather onto the other pan of the scale. The heart starts to grumble. Ramesses is fearful that it’ll tell tales about the anger and cruelty of his life. So he quickly activates the spell he’s been told will silence it. He lets out a long breath as the heart subsides. Osiris smiles at him. Well done.

The feather and the heart remain in balance. Osiris produces another scroll, and compares it to the ba. Then he asks the first of the forty-two questions. “Have you committed a sin?”

Ramesses makes sure the right spell is activated and quickly replies. “No.”

The list includes having slain people, terrorised people or stolen the property of a god, all of which Ramesses knows he’s done, but the spell lets his lies go unchallenged. One of the questions is whether or not he’s felt remorse, which makes him feel particularly vindicated. He may not have changed the Duat, but it has not changed him.

Osiris reaches the end. The feather has remained in balance with the heart. He smiles again, and holds up his own spell jar to show Ramesses. On it is a communication from a Museum in Atlanta, who have bought him intending to set him free.

The transition finally happens on one of these people’s flying machines, somewhere over the ocean. The context changes between the Duat and the mirror of heaven. Ramesses finds himself standing beside the crate containing his body, and here is Seti with him!

He laughs and cries, hugs his son to his breast. They are both themselves again. “The things the gods have put in place!” says Seti.

“I liked your Institute,” says Ramesses.

“They do their best,” says Seti, stroking his father’s hair.

“The Book of the Dead” copyright © 2013 by Paul Cornell

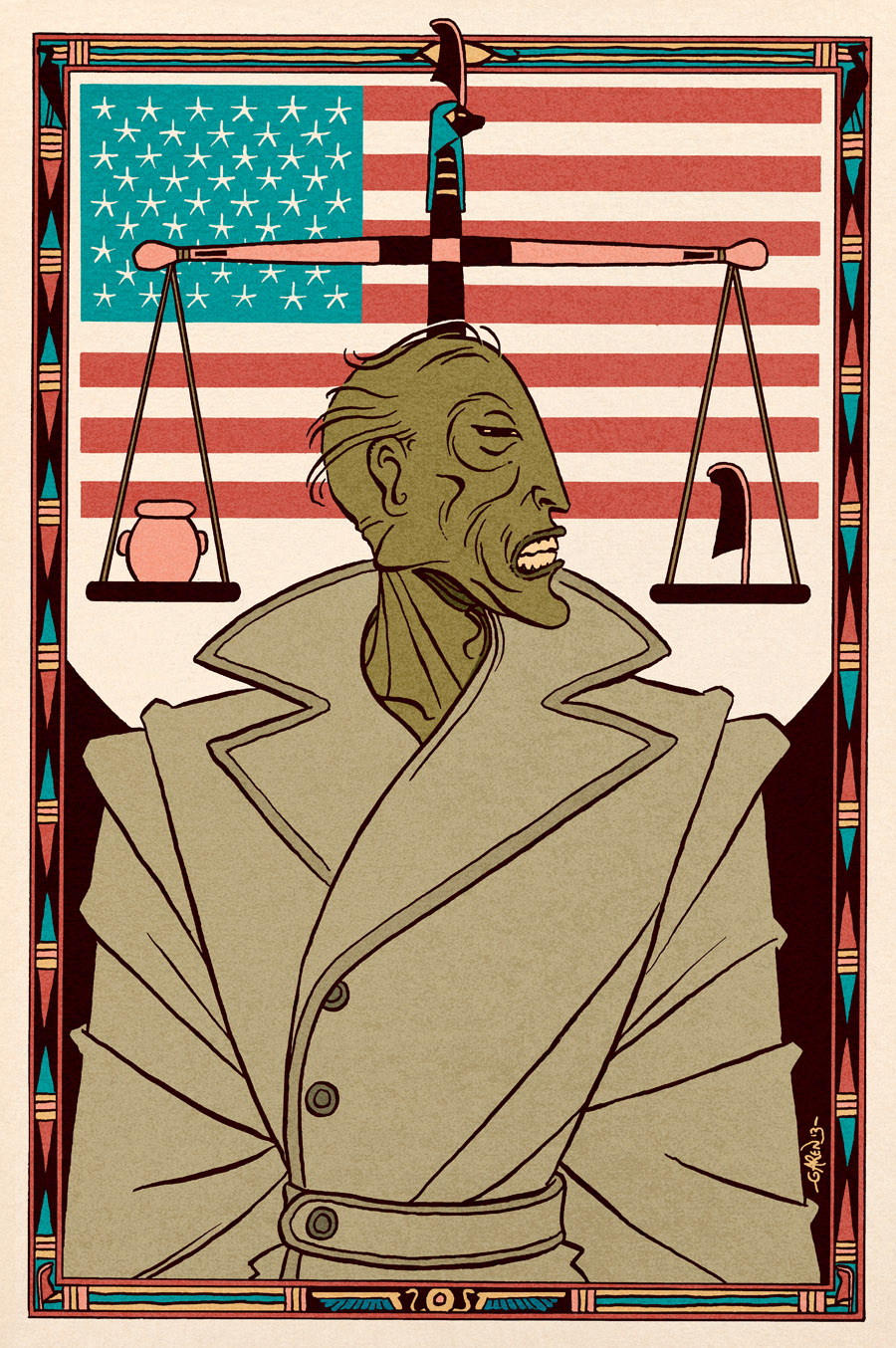

Illustrations by Garen Ewing